|

U.S. Beaumont genealogy |

U.S. Dr. William Beaumont's |

U.S. Dr. William Beaumont's birthplace |

U.S. Admiral Melancton Smith |

Canada's Dr. William R. Beaumont |

Admiral Melancton Smith was the son of Colonel Melancton Smith and his first wife, Cornelia Haring Jones. After Cornelia's death, Colonel Smith married Ann Green, sister of Deborah Green Beaumont. Colonel Smith died in 1818 at

This web page contains the text for Rear Admiral Melancton Smith, U.S.N. - A Memoir, written by Reuben Gold Thwaites, Secretary of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Our deepest thanks to Paul Hass, Senior Editor of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, for granting us permission to post the memoir here.

Thwaites' text is printed below in its entirety, with the original page endings preserved. The photos, images, and captions have been added to this web page version.

Rear Admiral Melancton Smith, U.S.N. - A Memoir, by Reuben Gold Thwaites, Secretary of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Published 1893 in Madison, Wisconsin; Pamphlets in American History series.

THE RECORD.

Born — New York City, May 24, 1810.

Midshipman — March 1, 1826.

Passed Midshipman — April 28, 1832.

Lieutenant — March 8, 1837.

Commander — September 14, 1855.

Captain — July 16, 1862.

Commodore — July 25, 1866.

Rear Admiral — July 1, 1870.

Retired list — May 24, 1871.

Died — Green Bay, Wis., July 19, 1893.

Above left to right: Robert R. Livingston, Melancthon Smith, and Governor George Clinton (anti-Federalist) shaking hands with Alexander Hamilton (a Federalist). Admiral Smith's grandfather Melancton (Melancthon) Smith helped reconcile Federalists and anti-Federalists, enabling New York state to ratify the U.S. Constitution in the Dutchess County Courthouse in Poughkeepsie on July 26, 1788. |

Rear Admiral Melancton Smith came of good stock. His paternal grandfather, also Melancton Smith (1744-98), represented the County of Dutchess in the first Provincial Congress of New York (May, 1775), of which body he was a distinguished member; he was captain commandant of the militia (1776) of Dutchess and West Chester, first sheriff of Dutchess (1776-80), and later a judge of the common pleas. In June, 1788, he represented Dutchess in the Poughkeepsie convention, wherein was considered the newly-prepared Constitution of the United States. He was one of the leaders of the opposition to this instrument. A man of powerful frame, an experienced and logical debater, quick at expedient and repartee, and with a caustic humor, he proved a foe worthy of Hamilton and Livingston. But when he learned, at last, that enough States had given in their adhesion to secure the adoption of the Constitution, Smith gracefully yielded, amid the plaudits of all save his friend Governor Clinton, who stoutly held out in opposition to the end. Bluff old Melancton Smith was one of the original proprietors of the Plattsburgh Old Patent, holding title to 1,120 acres, and was thus (1784) one of the founders of that town, although his

actual residence was, for the greater part of his life, in New York City, where he died.

In 1811, Plattsburgh entered upon a career of prosperity, and thither the smith family removed that year. Melancton Smith's son, the second Melancton (1780-1818), married Cornelia Haring Jones, daughter of a prominent physician of Welsh descent, Dr. Gardener Jones. To them, May 24, 1810, was born in New York City, the third Melancton (1810-1893), their youngest son, and the subject of this memoir. Melancton the second carried out the traditions of the family, and served his country faithfully and efficiently through the War of 1812-15, as a colonel of infantry; he commanded Fort Moreau, the principal garrison at Plattsburgh, during the battle at that place; while his brother Sidney was at the same time a captain in the navy, under McDonough, and won high honors in the Battle of Lake Champlain (Sept. 11, 1814).

With such ancestral backing, and his earliest years spent amid such stirring scenes, it was no surprise that the third Melancton should display a taste for the armed service of the nation. Having received an academic education, he entered the navy as a midshipman, in his sixteenth year (March 1, 1826) and, at first on the frigate Brandywine, and later on the sloop-of-war Vincennes, made a round-the-world cruise of four years' duration. In the course of this vigorous introduction to his

calling, he visited the then far-away savage South Sea Islands; and was one of the first of American sailors in the ports of China and Japan, countries in his day but little known of Christendom. Upon his return in 1830, the stripling of sixteen developed into a robust and well-trained navigator, he was for a time sent to the New York naval school, but soon was again in active service, being stationed in the West Indies in 1833-35, at the New York Navy Yard in 1836, and again in the West Indies in 1837-38. Commissioned as a lieutenant in 1837, he was attached to the Coast survey steamer Poinsett, during the closing year of the Seminole War (1839). While on the east coast of Florida, he at one time commanded a battery, and a twenty-oared barge on the Florida Miami.

Interspersed with occasional services at the navy yards of New York and Pensacola, Lieutenant Smith had his full share of duty at sea. Among the most interesting of his early experiences were those with the sloop Fairfield, in the Mediterranean, during 1841-43, and with the famous old frigate Constitution, also in those waters, in 1848-51. While upon this latter cruise, he obtained leave of absence from his ship and made an extended tour of Egypt and Palestine. This was long before the days of Cook's excursion steamers on the Nile, and railroad trains to Damascus and Jerusalem, and the trip was one requiring great

effort and powers of endurance. The adventurous lieutenant of the Constitution, now a man in early middle life, was well equipped by study and historical insight to enjoy his expedition to the utmost, and returned with the zeal of an Orientalist to archaeological studies which occupied much of his attention for the rest of his years.

In times of peace, promotions in the armed service come slowly, so that it was not until 1855, after twenty-nine years of useful and active naval life, that our hero was commissioned a commander, although for several years previous to this he had been executive officer of the Potomac. The rest of the years until the opening of the War of Secession, Commander Smith served as light-house inspector, a position involving hard work and much responsibility.

It was no doubt with some degree of professional satisfaction that the officers of both army and navy received their orders to enter upon active service in defense of the country. With the exception of the little flurries of the Seminole War and the Mexican War, the navy, in particular, had had little to do in the way of fighting, since 1815, and an entire generation of naval officers had sprung up since that. It was not thought that the Rebellion would long withstand the northern arms, but a short, sharp brush with an actual enemy was not unwelcome to the loyal tars. When, in May

Admiral David G. Farragut, commander of the Union Navy on the lower Mississippi. Photo taken between 1860 and 1865; he became Vice-Admiral December 3, 1864. He first served in the War of 1812. |

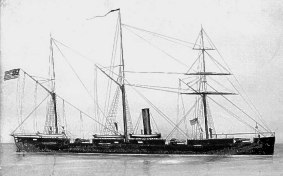

(1861), Commander Smith was ordered the join the Gulf blockading squadron with his steamer, the Massachusetts, he lost no time in getting to the scene of action. September 16th, he had a sharp engagement with the fort at Ship Island, Miss., in the course of which he repulsed the attack of three Confederate steamers and a revenue cutter, which were protected by the guns of the fort. Under the Massachusetts' heavy fire, the Confederates evacuated this important stronghold, which formed the water communication between New Orleans and Mobile, and the next day a landing party from the steamer took possession of the deserted ramparts. Later (October 26th), he had a fierce duel with the Confederate steamer Florida, in Mississippi Sound.

While doing notable service with the Massachusetts, it was not until 1862-63, while in command of the steam sloop Mississippi (twenty-one guns), that Commander Smith won his brightest laurels. His ship was in Farragut's fleet, operating on the lower Mississippi river. The passage of Forts Jackson and St. Philip (April 24, 1862) was a perilous task, the Mississippi having eight shots pass clean through her. The rest of the story is best told in Farragut's own simple words, in the official report:

"Just as the scene appeared to be closing the [Confederate] ram Manassas was seen coming up, under full speed, to attack us. I [Farragut]

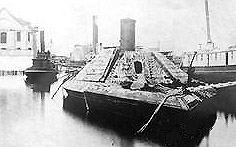

The Confederate ironclad ram Manassas had a convex plated top which deflected cannon shot; its hull was only two feet above the water, making it a tough target. It was fast-moving and almost bomb-proof, and Union intelligence called it a "hellish machine." On April 24, 1862, after Smith forced it aground (where its crew escaped) and poured broadsides, the Manassas drifted down the river in flames, exploded, and sank. |

directed Captain Smith in the Mississippi to turn and run her down. [Smith had, however, first signaled for permission to do so.] The order was instantly obeyed, by the Mississippi turning and going at her at full speed. Just as we expected to see the ram annihilated, when within fifty yards of each other, she had put her helm hard aport, dodged the Mississippi, and run ashore. The Mississippi poured two broadsides into her, and sent her (the Manassas) drifting down the river, a total wreck. Thus closed our morning's fight."

Commissioned as captain in July following, Smith remained in the Mississippi, taking part in all of the many exciting engagements of the squadron. In the spring of 1863, Grant was painfully approaching Vicksburg by land, and Farragut had orders to cooperate with him on the river. The Confederates had strong works at the high bluff of Port Hudson [in Louisiana], the banks being lined for three miles with tiers on tiers of batteries. Farragut, in connection with a land force of twelve thousand men under Banks, determined to run by the terrible batteries of Port Hudson and recover control of the river between that point and Vicksburg. Never before had Farragut and his commanders been put to a test like this, and friends and enemies alike held their breath in admiration, while the wooden vessels of the Union prepared, the night of March 14-15, to steam through this valley of flaming death.

Lieutenant George Dewey was Smith's executive officer on the Mississippi. To abandon the burning ship, Smith had to evacuate almost 300 men with only three useable lifeboats. Smith and Dewey personally searched the ship for wounded, before leaving in the last lifeboat shuttle. That night, only one Union ship got past Port Hudson. Dewey later became the only "Admiral of the Navy." |

First came the Hartford (flag ship) and the Albatross, lashed side by side; then the Richmond and the Genesee, and the Monongahela and the Kineo, while the rear was brought up by the Mississippi and the Sachem. It is a stirring story, that tumultuous attempt to pass the batteries, but there is no space here to speak of it in detail. The heaviest fire appeared to be centered on the Mississippi, which, when her commander thought the passage about over, lost her course and struck bottom. As she lay there immovable, the Confederate batteries fairly vomited fire and shell upon her, and her decks were soon covered with dead and wounded. Captain Smith, as calm in this pandemonium as on parade, expended almost superhuman efforts to get his vessel off; but seeing at last that this was impossible, carefully set fire to her in several places, spiked the guns, and lighting a cigar, coolly but quickly got his men into the boats with his sick and wounded. The last man to leave the burning craft, he soon had his party on board the Essex, which had, through the tempest of shot and shell, gallantly come to his relief. Lightened by the removal of the crew, the Mississippi, now wrapped in sheets of flame, swung clear of the bar and came steadily and swiftly down the current. One of her broadsides had not been discharged, and the guns, now heated in the blaze, with a terrific roar, poured their missiles against the

The USS Monongahela was commissioned in January 1863 and was built as shown above, with three pivot guns and no bowsprit. The lower Mississippi River was its first service. After the Mississippi was lost, Smith became captain of the Monongahela and George Dewey became its executive officer. |

hostile batteries. Just below Prophet's Island, the fire reached her magazine, and the grand old vessel, ablaze from topmast to waterline, all of a sudden went skyward with the boom of an earthquake, and fell in a shower of flame, a monster pyrotechnic display.

The passage of the batteries was not effected; but the attempt, and Captain Smith's part in it, will ever live in our history as a thrilling deed of heroism. It is perhaps needless to add that Admiral Farragut and the Navy Department warmly approved his course, and spoke with admiration of his cool and courageous bearing, although the commander himself, to his dying day, never mentioned the loss of his favorite Mississippi but with moistened eyes.

On the night of October 27-28, 1864, the ironclad Confederate Ram Albermarle was sunk at Plymouth, North Carolina by a spar tarpedo from Picket Boat Number One (a steam launch) led by Lieutenant William Barker Cushing, then |

Given command of the Monongahela, Captain Smith participated in the unsuccessful general assault by Banks and Farragut on Port Hudson, during the closing days of May, being among the foremost in the naval attack.

In January following (1864), he served on the Harriet Lane court martial, and soon afterward we find him in charge of the Onondaga, on the North Atlantic blockading squadron. After cooperating with General Butler in the military movements at Dutch Gap and Deep Bottom, he was sent to look after the Confederate ram Albemarle, which was infesting the North Carolina sounds and imperilling the Union squadron there. He sighted her (May 24th) in Albemarle Sound, just after she had

The USS Onondaga on the James River, Virginia in 1864. It was the first double-turreted monitor completed for service, commissioned in March 1864. (The foreground shows soldiers in a rowboat.) In 1867, its builder bought it back and then sold it to the French Navy. |

sunk the Union Southfield. The Onondaga was supported by several armed vessels, while the enemy had with him the armed steamer Bombshell and a convoy ship filled with troops. The engagement was of a desperate character; the Bombshell was captured, but the Albemarle, though badly riddled, escaped.

The Wabash was inactivated in February 1865, the month after the second attack on Fort Fisher, North Carolina. It was Smith's last ship. This photo was taken from the deck of the monitor USS Weehawken, in Port Royal Harbor, South Carolina, 1863. |

By this time, Captain Smith had honestly won recognition by the Department as one of the most gallant of our naval fighters; while all who served under him, officers and men, had come to regard him with a warmth of affection that was notable throughout this branch of the public service. In July he was made divisional officer on the James River, with the Onondaga as his flag-ship. October found him in command of the steam frigate Wabash, in which he participated in two attacks on Fort Fisher, Dec. 24-25, 1864, and January 14-16, 1865. The last assault was especially vigorous, and in it the Wabash lost eleven killed and wounded, besides a good share of the storming party sent out from it.

Much of the rest of the year 1865 was spent in court martial duty, closing up the affairs of the Department consequent upon the declaration of peace. He was commissioned as commodore in 1866 (July 25th) and appointed executive officer of the Washington navy yard — later, its commandant. In 1866 (September) he was appointed chief of the Bureau of Equipment and Recruiting, in the Navy Department. In

1870 (July) he received his commission as rear admiral and was placed in charge of the Brooklyn navy yard. The following year (1871) the gallant sea dog was placed on the retired list, being then sixty-one years of age, and made a governor of the Philadelphia naval asylum, which position he filled until the passage of the act of congress relieving retired officers from active duty except in war.

And thus passed the forty-five years of Admiral Smith's eminently active and useful naval career. It is said by those who knew him when a child, and through his boyhood years, that he never appeared to know the sensation of fear, which peculiarity was occasionally tested in a ruthless way by his companions. In peril by sea and land, twice shipwrecked in the Gulf of Mexico, twice brought low by yellow fever, cruising among pestilential islands and along death-breeding coasts, as a mere stripling having part in the Florida War, and engaged from beginning to end in the War of Secession as a commanding officer and amid its wildest scenes, he yet escaped mortal injury and fatal disease. Eighty-three years and three months found him with none of the usual infirmities of old age, no dullness of the ear, no loss of vitality in his step or manly bearing in social life, — no shadow over intellect or memory. He was to the last in full enjoyment of the busy world around him, especially watching with interest and

amazement the great advance in naval architecture and appliances for modern warfare at sea, which are perhaps the most distinctive marvels of this closing decade of the century.

It was my good fortune to be thrown into somewhat intimate social relations with Admiral Smith during the last few summers of his life. True heroes are ever modest, but he was preeminently so. In him there was nothing affected in this sinking of self. His modesty was innate, he shrank from public exhibition: what he had done was simply in the line of duty, and merely to be treated as impersonal events in our national history, which any other man, similarly situated, would have brought about as a matter of course. In appearance and manner, he was distinctly of that gentle class which each succeeding generation fondly styles the "old school." Tall and supple of form, stately in bearing, of courtly grace, cosmopolitan in taste, keen and witty of speech and kindly in expression, fond and a rare critic of literature and the fine arts, and a charming conversationist, Admiral Smith was to the last an ornament to cultured society, and an inspiring example to American youth, — an honored son of an honored ancestry. He was married in 1837 to Mary Jackson Jones, daughter of Thomas Jones, of Long Island, and a niece of the two late chancellors of the City of New York, Hons. David S. and

Samuel Jones. Mrs. Smith died at their country seat, at Seaford, Long Island, the fifteenth of April, 1885.

Admiral Smith passed away at "Hazelwood," the home of his sister, — Mrs. Elizabeth Smith Martin, of Green Bay, Wis. — on the nineteenth of July, 1893, after two days of acute pneumonia, aggravated by a heart ailment of some years standing. His sufferings were borne with that patient endurance which had marked his entire conduct when adverse and painful circumstances entered upon his life. Entering his country's service sixty-seven years ago, there are probably few now living who have been for so prolonged a period on the national roll of honor; while even of those who came to the defence of the Union so late as thirty-two years ago, when Captain Smith was almost old enough to be retired, there are now few with us who served her with such distinguished credit.

This warm-hearted patriot, this honorable and courteous Christian gentleman, believed by all manner of men who once had known him, and who seemed to remain among us as an inspiration from a former generation, was laid to his final rest in the beautiful cemetery of Woodlawn, at Green Bay, his warfare over, the victory won.